With coalition governments at the helm during the ’70s and ’90s, Türkiye’s political landscape was mired in instability, which provided a pretext for the military to topple or intervene in civilian rule.

The coalition governments resulted in political deadlocks and gave rise to a slow-moving bureaucracy in state affairs.

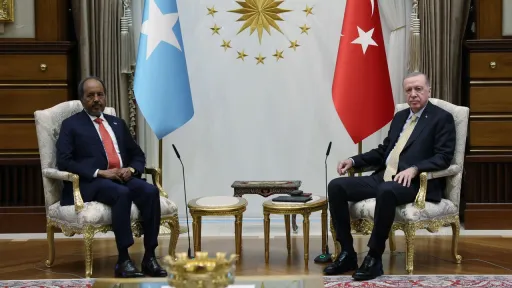

In 2017, after yet another coup attempt in the previous year, Türkiye under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, moved to change the country’s parliamentary system to a presidential model.

Erdogan described the new system as a Turkish-type presidential system, believing that this model could also inspire other countries.

Türkiye will face an important election cycle on May 14, when the country will hold both parliamentary and presidential elections. Many analysts think that the results might also indicate the popularity and strength of Türkiye’s presidential system.

Türkiye’s new system has some similarities and differences with the French semi-presidency and the American model. While some political analysts see France as the best example of a semi-presidential system, the US stands as a powerful representative of a full presidential system.

Here is a simple comparison of the Turkish presidential system with its French and American counterparts:

Presidential elections

In Türkiye and France, the presidential election has two rounds, unlike the US, where the country’s head of state is elected in a single decisive vote.

In France and the US, parliamentary and presidential elections are held at different times, while Türkiye holds both polls on the same date.

Office of the prime ministry

Like the US, there is no prime ministry in the Turkish presidential system. While the Turkish president can appoint cabinet members directly, the US president can nominate ministerial positions subject to the American Congress’s approval.

As a result, in Türkiye and the US, the president has exclusive authority to choose who will lead almost all government areas, from foreign policy to domestic and economic decision-making.

In France, the president appoints the prime minister from members of the majority party. France’s prime minister-led government is subject to the approval of the parliament, which can also remove it with a vote of no confidence.

In France, defence and foreign ministers are usually left to be appointed by the president, while domestic and economic policies are under the authority of the prime minister, who can nominate respective ministers of the cabinet.

As a result, the French system is called a semi-presidential model, unlike the US, which is a full presidential system.

A semi-presidential system shows similarities to a parliamentary model, which is practised by countries like the UK, Germany and many other Western countries. But a head of state in semi-presidential models has unusual powers unseen in parliamentary systems thanks to the political reality that he/she is elected by popular vote.

While presidents are officially heads of state in parliamentary systems, they are elected by national assemblies. Due to the lack of a popular vote mandate, the presidential office of parliamentary systems holds ceremonial political roles in leading the government.

Authority of dissolving parliament

The Turkish presidential system shows differences from the US system regarding dissolving assemblies. While the president can dissolve the Turkish parliament, this is not the case in the US, where the president has no authority to dissolve either the Senate or the House of Representatives, the two legislative chambers of the Congress, under any circumstance.

In this sense, the Turkish system is similar to the French system in which the president can dissolve the National Assembly at any time after consulting the prime minister and leaders of both the upper house (Senate) and the lower house (National House).

Removing the president

In terms of removing presidents from their office, the Turkish system shows more similarities to the US than France.

In the US, Congress can impeach the president with a simple majority vote, but in order to remove the president from his/her office, a two-thirds Senate majority is required.

In Türkiye, the Turkish parliament can call for a fresh presidential poll if a three-fifths majority votes to decide so.

In France, removing the president, which is called destitution, requires a simple majority vote in both chambers of the parliament, unlike the Turkish and American systems, which enforce a supermajority – two-thirds or three-fifths majority – for changing the head of state.

If both upper and lower houses decide to remove a French president, the Constitution’s Article 68 stipulates that only the Parliament “sitting as the High Court” can do so.

Calling referendums

Unlike the US model, which has no referendums at the federal level, both Turkish and French presidential systems allow referendums at the national level on crucial issues like constitutional changes. At the local level, France and 23 American states authorise referendums on various issues, while the Turkish presidential system has no such clause.

In France, a referendum may be called on any issues by the president “without countersignature”, according to the constitution. The French president can also call a referendum on a proposal by the cabinet or the parliament.

Lastly, a referendum in France can be called by “one-fifth of the members of Parliament, supported by one-tenth of the voters enrolled on the electoral lists” on subjects related to government bills affecting the functioning of government institutions.

On the other hand, Turkish referendums might be called on constitutional changes directly by the president. In Türkiye, additionally, when a constitutional amendment does not receive the required majority in parliament, it needs a referendum vote without the president’s intervention.

Referendums have played important roles in both Turkish and French politics.

Türkiye’s transition from the parliamentary system to the presidential model was approved by a critical referendum held in 2017. Similarly, France’s move to its semi-presidential system through the 1958 constitution was also approved by a referendum held in the same year. France’s entrance to the EU also happened through the Maastricht Treaty referendum in 1992.

Appointing ambassadors

The president has direct authority to appoint ambassadors in Türkiye and France.

But the situation in the US, where the president “shall nominate” ambassadors “by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate”, according to the constitution, is different. As a result, an American ambassador’s appointment is subject to the US Senate’s approval.