By Emmanuel Onyango

For Haitians, a proposal by Kenya to lead a multinational force to restore order in the country sounds all too familiar.

Their land is in the grips of widespread gang violence and political instability. After months of mounting violence, families have fled from gangs controlling large parts of the country.

At the same time, vigilante groups in the violence-riddled capital Port-au-Prince have taken up machetes and batons to fight back.

However, they have not been able to successfully tackle the gangs that are armed with assault weapons mainly sourced from the US, according to reports. The armed groups have also out-gunned the local police.

Gangs have been causing insecurity in Haiti for decades. Still, the violence has worsened since the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in 2021, created a power vacuum and left armed groups competing for control.

The violence, including kidnappings for ransom, has damaged infrastructure and disrupted critical services such as healthcare and education.

This year alone, 2,400 Haitians have been killed and hundreds of others abducted, according to the United Nations.

Kenya's listening ears

As things stand, Haiti has yet to elect representatives after the term of senators expired in January.

Amid the lawlessness, Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry appealed for an international intervention to restore order in the country. He got the backing of the United Nations, the US, and its allies.

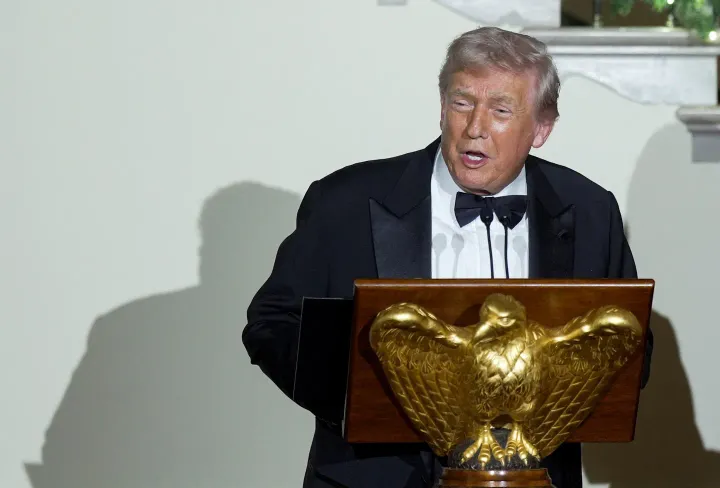

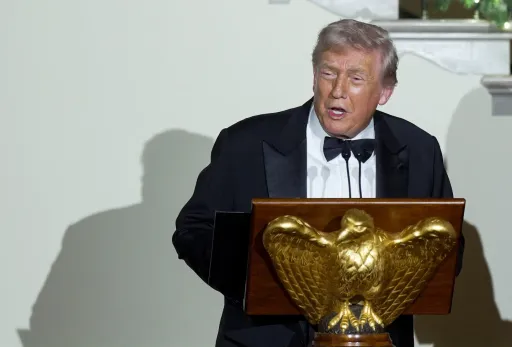

Following the signing of a deal with the United States earlier this week, Kenya has agreed to send an intervention force of 1,000 police officers to help neutralise the gangs and bring about peace.

The US is expected to fundthe deployment. The proposal is awaiting approval of the UN Security Council.

Kenya's President William Ruto said his government was responding to Haiti's call for assistance and that the mission is a pan-Africanist venture in solidarity with Haitians.

The outlined roles of the force are to guard installations, provide operational support against gangs and train Haitian police.

"The cry of our brothers and sisters has reached our ears and touched our hearts," Ruto told the UN General Assembly.

Kenya's local problems

Foreign Minister Alfred Mutua told journalists last week that other African nations might be coming on board.

However, analysts have mixed feelings about the mission. Some argue that it is geared towards Kenya's ambition to raise its profile on the international stage but at the cost of projecting US interests following reports of initial difficulty in staffing a US-backed global force for Haiti.

"The premise is wrong, the thinking is wrong. First, the lack of capacity is an issue. Secondly is the dependence on the goodwill of some foreign forces," Prof Munene Macharia, an international relations expert based in the capital, Nairobi, told TRT Afrika.

Kenya has its own unmet security needs as it faces regular cross-border attacks from the Al-Shabab terrorist group based in neighbouring Somalia.

The group's attacks have flared up in recent months, with over 90 incidents of violence recorded in the border area targeting security forces and civilians, according to a report by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (Acled).

Haiti's dignity

Rights watchdogs have long accused the Kenyan police force of using excessive force against civilians while trying to address security challenges. The police often deny such accusations and insist on high accountability levels.

In Haiti, there is strong local opposition to deploying any international force. Gang leaders have warned that they will fight any global armed force deployed to the country. It will be a fight to save their "dignity and the country", one of them told international journalists last month.

During a previous UN mission in Haiti between 2004 and 2017, foreign troops were accused of gross human rights violations, and some Haitians still have memories of those alleged crimes.

"For Haitians, it's going to be mixed feelings. Peacekeeping efforts in the past have had a lot of human rights abuses and all the challenges that come with sending peacekeeping force in such a country," said Adam Bonaa, an African security analyst based in Ghana.

The language

However, he believes there is still hope. "We have to give the Kenyan government and the West the benefit of the doubt, hoping that this time around, things are going to be done right… we cannot throw our hands in despair and say that the issues in Haiti are beyond restoration," he told TRT Afrika.

But there is also the issue of language barrier. Kenya is an English-speaking nation, and its police officers are being deployed among a French-speaking population of nearly 11 million. Experts say this could make their operations more difficult.

"They don't speak Haitian Creole, and they don't know the terrain," said Prof Jemima Pierre, a Haitian scholar who teaches Africa and Afro-America studies in California.

"Do you think bringing in an armed force of people who don't speak the language, who don't know the reality in Haiti, do you think it is going to make it better?"

Some commentators suggest that a better start would be for Kenya to commit a smaller force proportionate to what some Caribbean nations joining the intervention are deploying.

Other analysts say what is more crucial for Haiti is support in rebuilding its understaffed and ill-equipped police force and re-establishing political structures to deal with the gangs instead of another round of deployment of foreign security forces.