On Wednesday, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global public health emergency over a deadly new variant of the mpox viral infection. Its detection and rapid spread in the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighbouring African countries has been described as “very worrying” by the WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

When the disease first came to the public’s attention, it was referred to by scientists as “the monkeypox virus.” Under pressure from public health experts, especially from African nations, the WHO changed its name to mpox on November 28, 2022.

Back then, the Lancet medical journal noted that “[a]long with a number of uncertainties and scientific issues, the outbreak has also brought to light unfortunate habits of our society: stigma, racism, and discrimination.”

People on online forums had been “making racist and unacceptable comments associating the name of the disease (“a disease of monkeys”) with African people. In addition to all the damage that any stigma entails, when it comes to infectious diseases, stigmatising population groups adds further damage, as it drives people away from seeking diagnosis, vaccines, and treatment,” the publication warned.

There is a long history of controversy surrounding names of diseases, and public health experts have been more cautious about not naming them after geographical locations, groups of people, or even animals which may not have anything to do with the disease, leading to horrific real-world consequences, along with misconceptions on the origin and spread of illnesses.

What's in a name?

For instance, the H1N1 pandemic of 1918-20 originated in Kansas, but became known as “the Spanish flu” due to “geopolitical forces” during the First World War (1914-1918), according to Rachel Withers, writing for Slate. “News of the outbreak was suppressed or heavily underplayed in Germany, France, the UK, and the US. But Spain, like Switzerland, was neutral in the war, and its media had no qualms about covering the contagious outbreak weakening its population, creating the false impression that this was a Spanish disease.”

Trisomy 21, or Down syndrome, was once called Mongolism. It took concerted efforts by geneticists and others to phase out the racist terminology before a neutral term was adopted in common parlance.

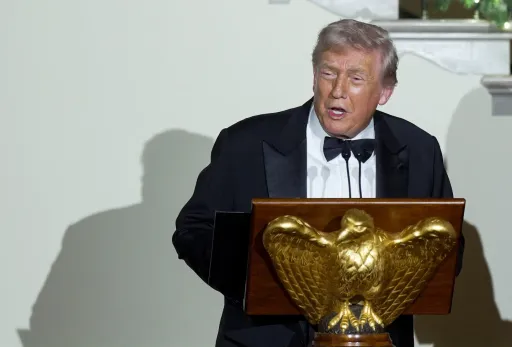

Closer to memory, in 2020, then US President Donald Trump would come under fire for calling the novel coronavirus “the Chinese virus.” Other terms used by Republican lawmakers included: “the Chinese flu”, “the Chinese coronavirus”, and “the Wuhan coronavirus.” Under criticism over the racist and xenophobic implications of these terms, Trump doubled down on his rhetoric.

“That name gets further and further away from China, as opposed to calling it the Chinese virus… without question, [it] has more names than any other disease in history…I can name… Kung Fu. I can name 19 different versions of names,” he mouthed off at a rally in Oklahoma in June 2020.

At the time, many felt his choice of words were a distraction from his administration’s poor handling of the surging number of novel coronavirus cases in the US. They felt he was shifting the blame, and endangering the lives of Asian-descent people in the US in the process. Between March 19, 2020 and June 2021, more than 9000 instances of 'anti-Asian' incidents were recorded by Stop AAPI Hate.

“Because it comes from China. It’s not racist at all, not at all” he defended himself in a press conference. “I want to be accurate.”

Yet the accurate WHO-designated terms would have been “Covid-19” or “SARS-CoV-2” and Trump’s insistence on calling it by any other name was inaccurate, harmful, and likely political. US-China relations have long been complicated and strenuous, as the two economic giants engage in a geopolitical tug of power and influence.

But to live in a “sane civilization”, the Lancet journal advised in December 2022, society must take responsibility “and severely condemn such unacceptable practices” in stigmatising diseases through their name. “Adopting neutral names when discovering viruses and their diseases is the first step, but certainly will not be the final solution unless we change human behaviour.”