By Marisa Lourenço

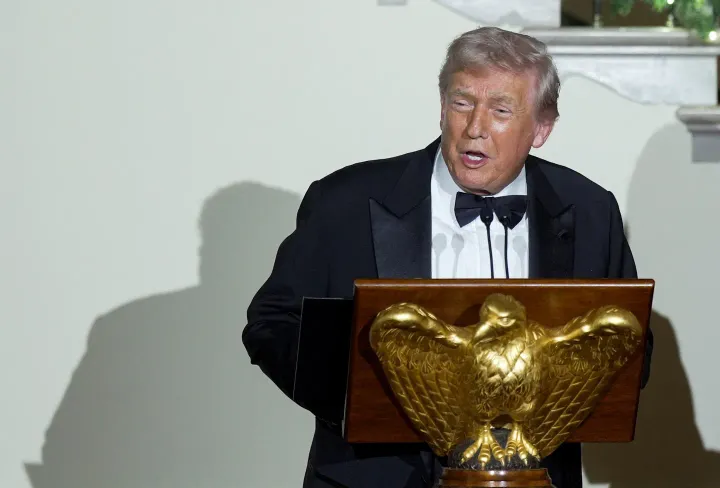

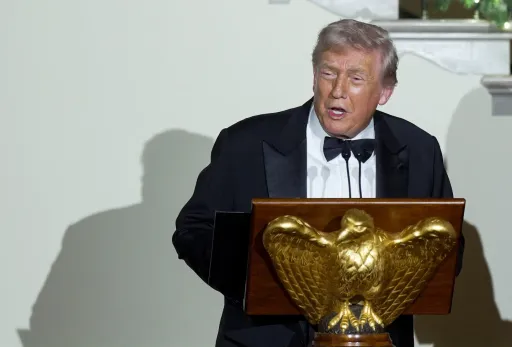

The US has been on damage control ever since relations between it and Africa declined under former President Donald Trump (2016-20), who failed to visit the continent throughout his four years in office.

This awareness is reflected in the US Strategy Towards Sub-Saharan Africa, released in August 2022, which outlines the country’s envisioned cooperation for the region.

In it, the US says it seeks to “reset its relations with its African counterparts, listen to diverse local voices, and widen the circle of engagement to advance its strategic objectives to the benefit of both Africans and Americans.”

This self-reflection has made for an ambitious strategy. The administration led by President Joe Biden since 2020 has made its most notable progress in two pillars of the policy towards Africa which are advancing pandemic recovery and economic opportunity; and supporting conversation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition.

As examples, it has formed partnerships with some African countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Kenya to accelerate primary health care in these countries, and contributed to the African Development Bank’s Sustainable Energy Fund in support of energy transition projects.

Biden also remained true to his December 2022 pledge to back the inclusion of the African Union (AU) in the G20, which was formally admitted at this year’s summit in September.

The strategy seems to have been developed with careful consideration, aiming to find a balance between the requirements of the region and the resources the United States is prepared to allocate.

Particularly commendable is the effort to work with non-partisan local and regional bodies, including the AU, Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), West African Health Organization, among others, and to support local journalists and lawmakers in tackling corruption.

It is worth noting that US foreign policy puts the American interests above any other but different administrations may adopt different strategies.

However, it seems the Biden administration has not considered the shifting geopolitical dynamics in how it engages with its counterparts.

Africa is not the same place it was under Trump, and some countries in the region now care less about what they mean to the US and more about what the US means to them.

Changing landscape

Part of this shift in attitude is down to anti-West sentiment across the region, elevated since COVID-19 vaccines became available at the end of 2022.

Developed nations hoarded the vaccine market to secure supplies for their own populations, even if this meant developing countries that could not afford to buy in bulk missed out.

India closed its borders to vaccine exports, too, in the midst of its second, brutal wave of infections.

Members of the global south, including governments in Africa, boldly decried on the world stage what they called vaccine nationalism.

This distrust has filtered into other areas, most notably in criticism of the West’s push for the world to abandon the development of fossil fuels in favour of renewable energy technologies.

Since the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), several African leaders have become more vocal in their assertion that their path to industrialisation should not be dictated by others, and lambasted developed Western nations for failing to provide the promised financing for energy transition projects.

There is also a growing trend of democratic backsliding in Africa, which has experienced eight military coups since 2020.

France has been the Western power of focus of this changing political landscape, owing to its role in colonial and postcolonial Africa.

There has been growing resentment over continued exploitation of African resources and political interference by the global powers especially those with colonial history in the continent.

New military leaders have also caused setbacks to democracy in some African countries further fuelling anti-western sentiments amid instability in those countries.

Limited power

No event has demonstrated the US’s failure to consider this changing landscape than its reaction to many African governments choosing to remain neutral in the United Nations General Assembly votes to condemn Russia in its ongoing conflict with Ukraine since February 2022.

At various points this year US Secretary of States Antony Blinken and Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen travelled to the region to urge governments to condemn Russia, arguing that abstention is akin to support.

South Africa has bore the brunt of this approach. It was accused by the US of supplying arms to the Russian government - an accusation a South African investigative panel found was false. US Ambassador Reuben Brigety who made the allegations also later apologised.

The Biden administration now seems to have toned down its aggression, but it took it many months to realise that its global dominance couldn’t force African governments into picking a side.

Earlier this month, South Africa hosted a summit on the US-Africa trade initiative known as AGOA in what many see as part of an attempt by the US to mend its relations with the country.

While the US is still a key trading partner to many African countries, there are multiple actors vying for influence in Africa as part of the changing global order.

It is clear that if the US is to realise its broader aim of resetting its relationship with Africa, it will need to accept the current global and African realities and learn to engage with a plurality of voices, including partisan ones.

The author, Marisa Lourenço, is an independent political analyst in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Disclaimer : The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of TRT Afrika.