By Toby Green

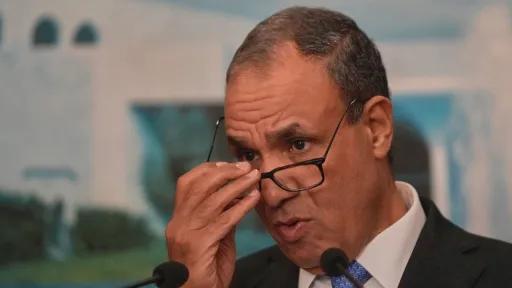

The news of Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s death on Wednesday has brought many reactions.

On the international stage, Kissinger is most infamous as the backer of the coup against socialist President Salvador Allende of Chile in 1973 – but he also drove key American policies during decolonisation, and especially in Portugal’s African colonies.

Kissinger’s aim was to bolster American power at the expense of African sovereignty.

He was the first US senior official to visit Apartheid South Africa in more than three decades, when as Secretary of State he made an official visit to South African premier John Vorster in 1976.

As the New York Times reported at the time, South African police killed as many as 7 Black students in the protests which followed.

This was part of a broader approach to southern Africa which was grounded in white supremacy, fear of communism and disdain for African lives.

During this 1976 visit, Kissinger intervened in South Africa to give Apartheid a major diplomatic victory, and was a close confidant of Ian Smith – leader of the white UDI government in Rhodesia.

Kissinger’s list of self-acclaimed “policy successes” makes grim reading fifty years later. In a memo to President Nixon in 1970, he described Congo as “one of our policy successes in Africa” – the left-wing President Lumumba had been assassinated with probable CIA backing in 1961 – and President Mobutu Sese Seko as having “made a reality of Congolese unity”. He had several subsequent meetings with Mobutu.

However, Kissinger’s major impact on the African continent came through his work to stymie the independence and autonomy of Portugal’s African colonies. Whereas former British, French and Belgian colonies had all won independence in the 1960s, Portugal – then governed by autocrat Salazar’s Estado Novo regime – fought to retain its colonies as part of its vision of a “greater Portugal”.

Indeed, many poor and illiterate Portuguese continued to migrate to Angola into the 1960s.

Before being Gerald Ford’s secretary of state, Kissinger had been President Nixon’s national security advisor. He was secretary of a National Security Council interdepartmental group which issued an African report on April 10 1969.

This favoured complete support of Portuguese colonialism, in spite of the wave of decolonization and the independence wars which had begun in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

Portuguese Prime Minister Marcello Caetano, of the Estado Novo regime (and former Minister of the Colonies) later indicated that US use of the Azores military base in the Atlantic was in play in return.

By the early 1970s, it had become clear that the Portuguese colonial wars were becoming unwinnable. It was indeed the hopeless situation of Portuguese forces in Guinea-Bissau which triggered the Carnation Revolution in Portugal on April 25th 1974, led by returned officers from the African wars.

Even so, Kissinger still moved in lockstep with the Portuguese government, and State Department memos from a July 1974 meeting show that he had said that the US would not vote for Guinea-Bissau’s admission into the United Nations unless this was supported by Portugal.

This prefigured Kissinger’s most catastrophic intervention, which came in Angola. Once the Portuguese colonial and settler forces had fled Angola in late 1974 and early 1975, the civil war began.

Although the communist MPLA were in the box seat, Kissinger intervened and supported backing South African efforts to arm opposition in the south – especially UNITA.

As the historian Piero Gleijeses wrote in his “anti-obituary” of Kissinger, this triggered what would become one of the most violent and bloody civil wars in postcolonial Africa. By October 1975, the intervention of Washington and Pretoria had reversed the tide of the civil war.

UNITA marched on the capital Luanda. But at this point Kissinger was blindsided by the intervention of thousands of Cuban troops sent by Fidel Castro from Havana in Operation Carlota: the Cubans turned the tide of the war and helped consolidate MPLA power in Luanda, the party which rules the country to this day.

Nevertheless, Kissinger’s intervention was a disaster for Angola. The civil war continued until UNITA’s final concession nearly 30 years later, in 2002. By then, between 500,000 and 800,000 Angolans had died and over one million had been internally displaced.

The South African-US axis remained until the battle of Cuito Cuanavale in 1988, fought against Cuban forces which had remained in Angola ever since Kissinger’s intervention.

With Kissinger’s death, one of the lynchpins in many postcolonial tragedies on the African continent has passed into history. We can now reassess the Cold War in Africa, and the way in which US interests sought to safeguard the structural economic framework for post-colonial looting.

Kissinger bolstered racism, and supported those such as Mobutu who would help the US to achieve its economic aims. With this era so vital to understanding the economic and political landscape on the continent today, an accounting of the impacts of his policies in Africa must already begin.

The author, Toby Green, is Professor of Precolonial and Lusophone African History and Culture at King’s College London.

Disclaimer: The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of TRT Afrika.

➤Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel for more stories.