By Charles Mgbolu

The Nigerian government has said there is no going back on its decision to end the fuel subsidy that made oil prices in the country among the lowest in the world.

It's a painful decision that has already had a bearing on the lives of ordinary Nigerians, sending prices of goods and services across the country skyrocketing.

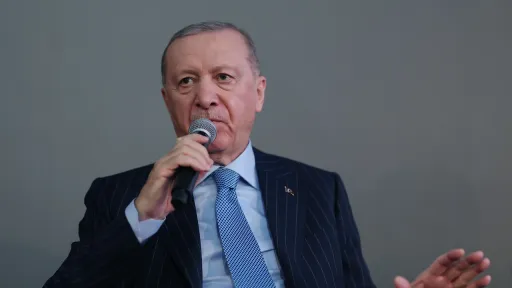

In his inaugural speech on May 29, Nigeria's new President Bola Ahmed Tinubu declared unequivocally that the spiralling cost of fuel subsidy – over $800 million a month on the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation's account and $10bn in 2022 alone – was unsustainable.

He said the rising subsidy expenditure couldn't be justified either as resources dwindle.

"We shall instead re-channel the funds into better investment in public infrastructure, education, health care, and jobs that will materially improve the lives of millions," Tinubu explained.

Subsidy on fuel had, for good reason, been an extremely popular policy, spawning benefits that directly and positively impacted living standards in the country.

As fuel prices stayed low amid inflationary tendencies worldwide, prices of goods and services in Nigeria remained within reach of the common man.

The government's announcement that it would stop subsidy payments, therefore, opened a Pandora's Box.

Spooked Nigerians raced to gas stations to stock up on fuel ahead of the impending hike, causing long queues to immediately appear at gas stations across the country.

The rush proved useless, of course, as fuel stations raised prices immediately after the speech.

The cost of fuel jumped more than 200% from $0.40 to $1.18. Some fuel stations outright stopped selling gas.

Thorny issue

Nigeria is an oil-rich country but it exports crudes and then imports refined products mainly from Europe because it lacks functional refineries.

This process contributes immensely to high costs of fuel and shortages as well. The subsidy is borne by the government to lower the price paid by energy consumers.

The state-owned oil company, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited says new fuel pump prices have been adjusted to reflect current market dynamics.

It was in 1977 that the Nigerian government introduced fuel subsidy to cushion the effect of rising global oil prices in that decade under the military regime of Olusegun Obasanjo, which promulgated the Price Control Act to regulate cost of various items, including fuel.

In 2012, former President Goodluck Jonathan announced plans to remove it, citing a need to attract more investors to the sector.

This sparked nationwide protests and economic activities grounded to a halt for two weeks.

Though many people now know and accept that subsidy payment is bleeding the nation, its removal affect the finances of individual Nigerians.

Feeling the pinch

"It isn't easy for us," Kenneth Umerie, a 29-year-old who resides in Lagos, told TRT Afrika. "Imagine paying double your daily fare on transportation, as I am having to do without any increase in my income? How do I survive?"

Another resident, Omolara Akerele, said the impact of the fuel subsidy being removed had distorted the basic functionality of everyday family life.

"My husband can no longer come back home after work because of transportation fares doubling," she laments.

"If he does so, we will have nothing left by the end of the month. Now, he has to sleep over at his friend's house, which is close to work, and only comes back once a week. It is heartbreaking for the children, who barely see him," Akerele adds.

Jide Pratt, an energy economist in Lagos, says there was no perfect time to remove subsidy.

"There will always be an impact on our finances because, as Nigerians, we have not been living in reality. We have not been paying the market value of the commodity."

He believes people are pained "because there has not been any clear communication that says this is what would be done with the savings accrued from the non-payment of subsidies".

Ripples in neighbourhood

Nigeria is not alone in this moment of self-realisation and painful discovery that fuel burns either way.

Its West African neighbour Ghana also announced in April that subsidy had been removed to stabilise its downstream sector.

But with Nigerians groaning under the sudden financial weight they have had to bear, labour unions have pumped up pressure on the government to reverse this decision.

A planned nationwide strike by the Nigeria Labour Congress was suspended only at the last moment as government negotiators raced to find a middle ground with different protesting groups.

While some feel that sustained pressure might turn the decision on its head, economist Pratt is convinced that President Tinubu won't back down.

"I believe Tinubu wants to correct narratives about himself prior to when he became President; so, he wouldn't say what he does not mean or things that he cannot implement," he says.

The President, perhaps, has a point to prove to critics who doubt his firmness to lead the country. Cementing this decision and proving its benefits would be an achievement carved to his name.

‘"But there is a need to have an index – if they say that fuel goes up by x amount, then x amount should go into salaries. We need to put something like that in place," Pratt suggests.

On May 22, policymakers and captains of industries from across the world assembled in Lagos for the commissioning of the world's largest single-train petroleum refinery with a capacity to process 650,000 barrels a day, built by the Dangote Group.

This has raised hopes for sufficient local refining of petroleum but the facility has not yet started operation fully.

"Fuel is a trigger for distillate. The more refining capacity we have in Nigeria, the bigger we will become as a net exporter and not an importer. This means more revenue, more exchange, and if the government is intentional about cutting wastage, then I think we will see joyful rebounds economically," Pratt says.