By Sylvia Chebet

At a hospital in the town of Soa, 20km from Cameroon's capital Yaoundé, cheers broke out as six-month-old Noah Ngah became the first in the facility to receive a new malaria vaccine called "RTS,S", the first of two groundbreaking formulations approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Noah's twin sister was next to get a shot of the recombinant protein-based vaccine, now being rolled out at scale across Africa after a nationwide launch in malaria-endemic Cameroon on January 22.

"Some parents are sceptical, but I know that vaccines are good for children," the twins' mother, Helene Akono, tells TRT Afrika.

Cameroon's pioneering malaria vaccine programme is being hailed as "a historic step towards broader vaccination against one of the deadliest diseases for African children".

Children under five years of age constitute the most vulnerable group affected by malaria. In 2022, they accounted for nearly 80% of all malaria deaths in Africa. Close to 580,000 deaths were recorded across the continent during the same period.

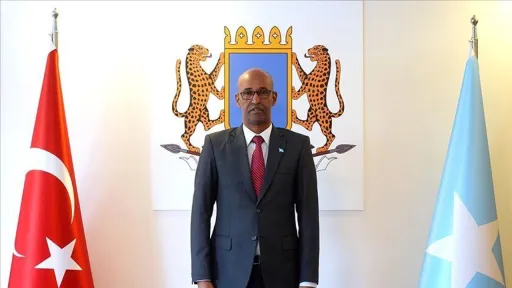

Africa CDC's deputy director, Dr Ahmed Ogwell, is convinced that once adequate doses of vaccines are available, mass vaccination will be the continent's best bet against the scourge of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

"Africa requires every tool that can contribute to fewer infections and people getting seriously sick, besides low mortality," he tells TRT Afrika.

Pandemic-induced disruption

Efforts to combat malaria were paying off, with global cases dropping by 29% between 2000 and 2019, before Covid-19 struck and disrupted health services worldwide.

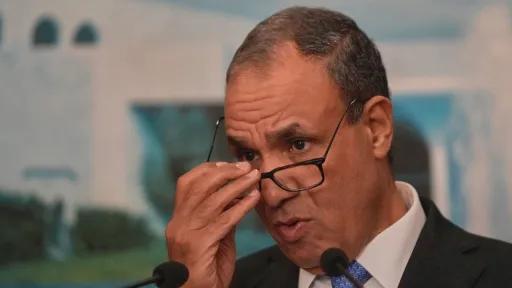

"Malaria mortality had decreased over that period by more than 50%, thanks to higher access to preventive tools and better diagnostics and treatment," says Prof Alassane Dicko of the Malaria Research and Training Department at Mali's University of Bamako.

The pandemic not only interrupted the steady decline but also reversed the gains as the focus shifted to battling the relentless surge of the novel coronavirus.

Malaria cases rose by 16 million between 2019 and 2022 — from 233 to 249 million, a 7% rise.

The medical fraternity is hopeful that the ongoing vaccination drive will significantly reduce the burden of malaria.

A pilot phase in Kenya, Ghana and Malawi, during which two million children were vaccinated, resulted in a substantial decline in severe malaria-induced illness and hospitalisations.

Kenya's End Malaria Council special advisor sees the vaccine rollout as a relief, albeit not "a silver bullet".

"Although it is saving lives, vaccine efficacy is not 100%. But even at 40%, it saves lives, especially in the age bracket where you tend to get severe malaria," he says.

Massive malaria spread

In Cameroon, 30% of all medical consultations are linked to malaria, reflecting how widespread the disease is in the Central African nation.

"Having a preventive tool like the vaccine will free up the health system and result in fewer hospitalisations and deaths," says Aurelia Nguyen, chief programme officer of GAVI, the global vaccine alliance.

In Africa, 19 other countries, including Burkina Faso, Liberia, Niger and Sierra Leone, are set to take Cameroon's lead and start nationwide vaccination programmes.

Besides the RTS,S vaccine developed by British drugmaker GSK, Oxford University's R21 is expected to hit the market soon.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus says having two vaccines for malaria will help close the massive gap between demand and supply, saving tens of thousands of lives.

Much-awaited R&D shift

Dr. Ogwell notes a growing interest in developing vaccines against parasites, whereas earlier research and development (R&D) would have been focused on combating viruses.

"The fact that we are going into developing vaccines for parasites is a big step, particularly for malaria, as it reduces hospitalisation and serious illness," he says.

Describing the vaccine rollout as a game-changer, he anticipates that starting vaccinations just before the high transmission season will significantly reduce future health costs.

Nevertheless, experts warn that traditional preventative tools like bed nets should not be ditched just because vaccines are available.

Prof Dicko says there are hurdles to surmount before Africa successfully eliminates malaria. "The current vaccines and other tools are not enough to erase malaria quickly," he tells TRT Afrika.

"African governments need to increase investment in malaria research to find more effective tools to control and eliminate the disease."

At the global level, researchers are working to develop vaccines with higher efficacy alongside better drugs for prevention and treatment.

Another critical area, as Prof Dicko points out, is "genetically modifying" mosquitoes so that they do not transmit malaria.

➤Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel for more stories.